Domestic Fetishes

Susan Andrews Grace

August 28 – October 31

Domestic Fetishes by Susan Andrews Grace

August 28 – October 31

In lieu of an opening night event, there will be a come and go style Open House with health protocols in place. No formal speeches at the event.

Friday September 25, 5 pm – 8 pm

Artist Statement

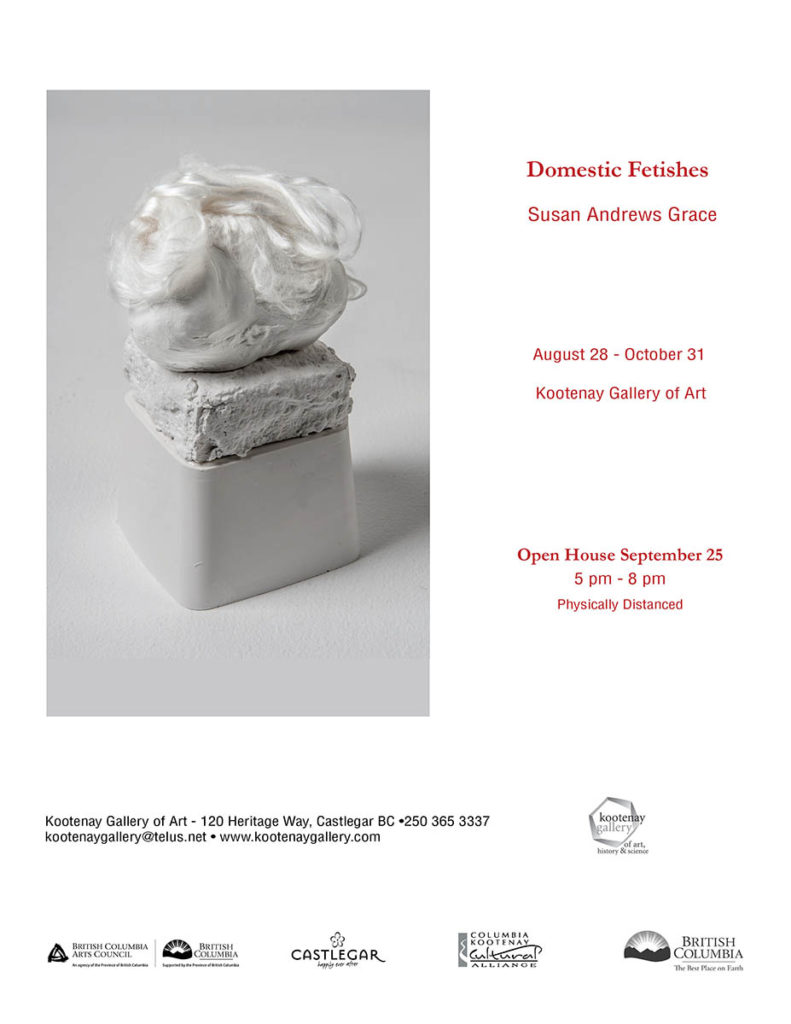

Domestic Fetishes are power objects relative to the world of an artist and woman who has done a heck of a lot of domestic work.

These are not the titillating fetishes of public imagination but more akin to the original fetish, an inanimate object used for spiritual purposes. My fetishes are made with the female gaze in mind and carry funny-bone benefits. They invite collaboration with the viewer in making sense of everyday objects and materials.

Domestic work is the ghost in our economic machine. It mirrors a rationalist separation between body and mind – essential yet unacknowledged and emotional labour that forms an invisible backbone to the larger economy. Childcare is but one example. Every day men, women, and children rappel the peaks and valleys of domestic mountains and molehills.

The installation of Domestic Fetishes means to represent the relative size of sperm (phalli) to egg (wedding dress) while deconstructing a few of the social mores surrounding conception and the resultant domestic realities.

Biography

Susan Andrews Grace’s visual art practice includes textile installation, mixed media, and sculpture. Her work engages historical and theoretical concerns about human existence. Andrews Grace considers cloth to be a powerful metaphor for the metaphysical and string technology an important example of human ingenuity. Her work contemplates the fragility of life in a human body.

Andrews Grace’s work has been exhibited in Canada and the USA over the last thirty years, mostly in public galleries. She has received grants from The Canada Council, Saskatchewan Arts Board, and CKCA for her visual work. She holds a BA (Phil.) and MFA (Poetry). She is also a poet whose sixth book, Hypatia’s Wake, (Inanna Publications, Toronto, York University) will be released in spring 2022.

Curator Statement

Maggie Shirley

Susan Andrews Grace is much like the art she creates: soft-spoken, unassuming, and similar to her name, gracious. She is also wickedly funny. The work in this exhibition is humourous and honest, as it plays with the dichotomy between archetypal images of gendered domestic roles and a more brutal truth.

Andrews Grace creates art that is full of contradiction. A poet as well as an artist, the work seems to whisper so the viewer leans in to bear witness. At that point Andrews Grace gives a “Gotcha!” that startles into re-viewing and re-thinking the direction of the artwork and the ideas into which she delves.

The artwork is primarily white, signalling purity, virginity, and cleanliness. The white is interrupted with more ominous seams of black and red. Is the home a sacred chamber or a battlefield? According to Andrews Grace it is simultaneously both, and then some.

There is a hint of sexuality that overlays the exhibition with objects such as the Phalanx of Phalli, cigars and revolvers bearing testicles and pointing suggestively, even aggressively up at the wedding dress of Femina domestica. Cycladic Nipples, one object from the series called Pantry Ghosts, includes a stack of baby bottle nipples. While leading some to breasts and eroticism, it also implies mothering, sleepless nights.

Cycladic Nipples reveals another layer of meaning. People of the Cyclades, one of the three major ancient Aegean cultures, were known for creating highly stylized, white marble figures of women, their arms folded protectively over their midriffs. Many of the figures are presumed to be pregnant. Are they representative of goddesses or merely, as some archaeologists theorize, dolls? This reveals some of what Andrews Grace asks about how we conceptualize women.

The focus is not solely on women. Andrews Grace offers a series of sculptures entitled Tattered, Torn & Worn. Rat Race features three collars from men’s dress shirts with a subtly-placed image of a rodent placed inside each one. While being a ‘domestic engineer’ is a tedious and difficult role for many women, so is being the primary income earner, a role that men in heterosexual, cis partnerships traditionally have held. For contemporary women the task of washing and ironing said collars still falls to them, as they simultaneously run in their own rat races.

In addition to the references to Cycladic culture, the work echoes other more contemporary artists as well. Andrews Grace cites the Arte Povera movement of Italy whose members created art using domestic materials as influential to her. In particular, Andrews Grace credits Alberto Burri and his use of burlap and gauze as a major source of inspiration. Thematically, the work stands with artists such as Louise Bourgeois, boldly sculpting the phallus and capturing the monotony of the role of ‘wife’. Andrews Grace aspires to be a rude version of Gathie Falk. And she’s definitely outrageous.

In many ways older women in our society are invisible. Susan Andrews Grace appears on the surface to play along with that role, while simultaneously thumbing her nose at those who would render her unseen

Background

Domestic Fetishes does some post-colonial sorting to understand objects such as jam jars, sorbet containers, or baby bottle nipples and in everyday rituals of human existence. The word “fetish” first came into use by sixteenth-century Europeans who called the ritual objects of non-Christian Africans, fetishes. Such objects were often handheld and were thought to grant their owners mysterious power over others, as they interacted with the natural world.

The term “fetishism” was eventually extended to describe non-Western art. Nineteenth-century thinkers Sigmund Freud, Karl Marx, and Alfred Binet contributed to our received concept of the modern fetish. My fetishes are handheld/domestic in size and definitely not “kinky”.

The post second world war movement of Arte Povera informs Domestic Fetishes. The impulse to use “poor materials” suits the female gaze: burlap, silk fibre, silk waste product (kibiso), plaster, concrete, wood etc. I want this work to be about how men and women work to create the safe places of procreation and childcare, and to marvel at the miracle of sexuality and conception. For example, Femina domestica and the phalli reflect the relative size of eggs and sperm.

Elements of Exhibition

Femina domestica: Wedding Dress, home-made, 1950s, ivory in wood (fir) cabinet/closet with holey walls, lit (7’ x 3’ x 3’). Dress is “fetishized”, with ribbons of beading

Veil: Wall-hung, on a hook

Garter: on the floor against the baseboard, caught by a pantry ghost

Phalanxes of Phalli: Fifty plaster and silk fibre pistols and cigars on four recumbent planks

Planks: Concrete, plaster, burlap, ink. Concrete bases (Tupperware bowls as moulds, inverted) The phalanxes are trained on the Femina domestica

Failed Testicular Forms: plaster and silk fibre on pedestals, on shelves

Ghosts from the Pantry: commodity fetishes— cast domestic objects: plaster, concrete, cloth, kibiso (silk waste product), paper string on conveyor belts/tracks made of stiffened burlap, on table

Bas Relief Panels: 3 (48”x24”) Acrylic paint, wood, some silk fibre on cradled wood panel

Red and White Quilts: 2 (48”x24”) Plaster, burlap, acrylic on cradled wood panel

White Panels: 4 (48”x24”) plaster and silk roving and kibiso, cloth on cradled wood panel

Tattered, Torn and Worn: Seven fetishes (styrofoam, plaster, buttons, antique cloth, thread, wire, string etc) on steel rod “pedestals”, 5’7” ft. high, concrete bases. Somewhat kinetic